Okay, reality and the gravity of Fall have set in since the last post. My subjective worship of Baltimore folks, be they poets or poetic will probably never be finished or formed properly and if it were there wouldn't be enough interest in it for it to see actual print, but it will be gathered so that at least when Ganesh gathers me in his kindly trunk for a cosmic ride off this brutal planet it will be assembled so that hopefully master archivist Megan McShea will place it in her file cabinet.

And no history of the Baltimore arts underground of the last 30 years would be worth its cyber space if it didn't contain praise to Laure Drogoul, one of the most single-minded hardest working visionaries. I wrote this piece for as an introduction for the booklet accompanying Laure's incredible art show "Follies Predicaments and Conundrums" that was at MICA, hosted by another Baltimore art visionary who I met while having panic attacks working at Kinko's in the early '90s - Gerald Ross.

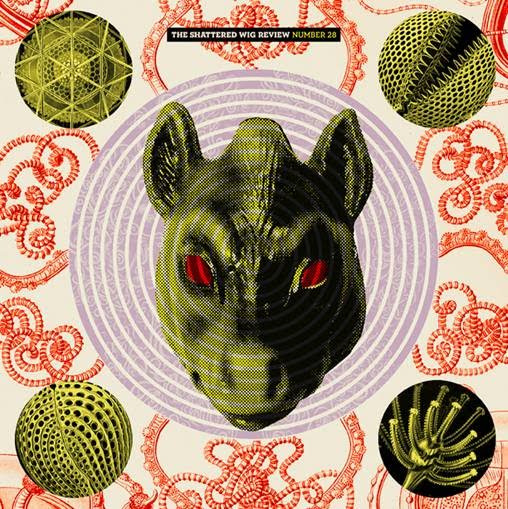

Even the flesh is a Mask;

Reflections In The Cobbled Spookhouse of Laure Drogoul

One of the many superhuman skills that Laure Drogoul possesses - the power of invisibility luckily not being one of them - is the ability to lift phone conversation to the realm of high art. You could be on your way out the door to the dentist's with an inflamed molar when you receive her siren call - the next thing you know hours have passed and your brain has tunneled through miles of subterranean neon brilliance and you suddenly know everything about an arcane insect species of whose existence you were previously ignorant. Plus, when you finally awaken to the "real" world, the one at your fingertips, you realize your molar no longer aches. When you excitedly run to the mirror to take a look at it you discover you now have the enormous chompers of a beaver.

It was during one such call, when we were discussing the poignantly strange and melancholic stories of the British author Robert Aickman, that Laure said, "There is a thin line between neurosis and enchantment." This not only summed up Aickman's work neatly, but, I also felt it was a key to the heart of Laure's art.

Take a look at the sinister but playful tower called Bozo Prison (for four or more), with mortal wretched clowns yabbering trapped inside a cage with a giant pointy-eared head on top. The mouth of the head contains skinny threatening teeth that look like ice-picks and suggest the act of devouring. Below this frightening head with glazed eyes rests an innocent, dainty bowtie. At this point of postmodern carnival symbolism, as surely as clown equals psychotic, bowtie equals intellectual or effete gone horribly wrong. Is the Bozo of the title referring to the prisoner or the keeper? Which do you relate to more? This is part edgy amusement park attraction chiding goofballs, and partmonument to fear of Outside Authority ImposingMores. Inscribed on the pedestal of the piece is the phrase Reception Diagnostic Classification Center, words that can be found outside Baltimore prison facilities. It brings to mind the awesome responsibility laying on one human's shoulders to pass judgment on another.

There is a Latin American short story called, The Psychiatrist, by Machado de Assis, in which the title character arrives in a small, rural town and starts pronouncing citizens insane one by one until he is the only one on the outside of the psychiatric hospital. Looking at the eyes of the head atop Bozo Prison brings that story to mind.

The installation piece, Evidence of Fairyland, is also perched precariously on that disappearing line between neurosis and enchantment, particularly the two pieces within it called Elf Skin and Pinocchio - realistic, stretched, and apparently treated for preservation - the "skins" are pinned and mounted. Part of what makes the popular cultural myth of fairies and Fairyland a Fairyland is its airy lack of science, but here is an unsettling display of supposedly magical, mythical creatures trapped and pinned up for all to see.

Does this evidence of magic buoy our spirits or does a chill run down our spine as we nervously look around for the nimble psycho who has perhaps killed these ethereal beings? Or, does the presence of these skins mean that even magic, if it ever truly exists, dies like everything else? When I attempted to gain insight into Drogoul's craft on these pieces, asking what she made them with to create such disturbing sheens, she immediately said, "Oh -homunculus skins, homunculus skins!" her irritation at my asking such a thing only half put on.

A self-described "interdisciplinary artist, cabaret hostess, olfactory spelunker and cobbler of situations," she's also a master of the comic nightmare viewed through a skewed lens of oddball science, an invoker of spirits who I'm sure keeps The Other Side up all night talking, and a macabre Energizer Bunny of production who has been a touchstone of underground avant-garde Baltimore art for more than twenty years.

Drogoul grew up in Tinton Falls, not far from Asbury Park, New Jersey. Her entry into, and apprenticeship in, the craft of the art world was a classic one. Near one of her bus stops when she was in eighth grade was an old grain mill run by a Hungarian man named Geza DeVegh, who was a painter and also had a gallery in the mill. There was a lively arts community that met and worked and socialized in the mill, including the painter Alice Neel who Drogoul met there.

At the mill, Drogoul learned to paint figures and landscapes in oil. While she was learning the craft of art in her hometown, her aesthetic was also being influenced and formed by nearby decaying American fun-land Asbury Park. She spent a lot of time exploring there and frequented the music clubs and gay bars. You can see the thread of fading carnivals and old America run amok throughout the entire span of her work, up to the present day.

One of her earliest performances/installations in Baltimore was a madcap piece called Ha Hay Hay Hamburgers at the first Ad Hoc Fiasco in Wyman Park. The Ad Hocs were high-spirited, anarchic celebrations of art and oddness in the early '80s - subversive and loose, but organized enough to draw outsiders in. Some of the biggest pulsing brains and ids of late 20th century art in Baltimore were launched there. Her piece involved renting and transporting cows and a calf from a man in Hagerstown who normally rented animals out to circuses. She installed the livestock inside a hamburger stand, where they were fed hay as she and an assistant made free hamburgers for the festival crowd. "I love animals," Drogoul says. "I love 'em alive, I love 'em dead."

Miss Construct Demonstrates Simple Domestic Chores from 1990 is another piece that turns American stereotype - this one of the hardworking housewife - into carny sideshow. Dressed in girdle and cinderblock boots, Drogoul chainsawed sticks of butter and beat eggs with a jackhammer.

But for me, the mother of all of Drogoul's amusement park style pieces is Dolly, a giant sculpture of an ominous Kewpie doll, pink with black ice cream dip hair and black toenails. On the back of its neck is a large barcode. It lights up at night and with its outstretched, pudgy baby fingers it becomes a Godzilla of cuteness. Most historians say the modern concept of romantic love began in courtly Europe in the Middle Ages. Dolly is the monster that concept has devolved into - a baby conceived of Elvis' frozen genetic wealth, half a ton of fat liposuctioned and dumped behind a cosmetic surgery clinic in L.A. and a quart of Britney's pill-enriched tears, marinated in the cathode rays of fifty years of TV sitcoms. It is the embodiment of pop culture's neurotic obsession with possessive love. "I love you, I love you" it repeats over and over from its pursed lips. You don't hear it at first because your therapist is talking loudly about self-actualization, but then you can feel the earth vibrate beneath your feet. You turn to see it, but it's too late, a giant pink foot has squashed you and the last thing you see before losing consciousness is the black blur of its barcode as it mechanically reels away pronouncing its love to the next victim.

Drogoul's more contemporary work mainly focuses directly on communication - Eternity through rituals and fellow humans through the olfactory senses. Her 2- channel video installation, Invocation for The Last Full Measure of Devotion (séance for patriots' dreams), at Arlington Art Center invoked the spirits of dead soldiers through the use of every military uniform used in American battles since the Civil War, ritualistic hand movements based on those used in the ceremony of the changing of the guards, a pentagon painted on the ground, and Drogoul singing When You Wish Upon a Star (When your heart is in your dreams, no request is too extreme/When you wish upon a star as dreamers do).

She also held many séances, including Séance for The Queen of Romania - for Dorothy Parker and invoked the spirit of countless waitresses who worked for one of Baltimore's most beloved old restaurants, Haussners, by re-creating the famous enormous ball of string they wound together over the many years of the restaurant's existence. She found the exact type of string they used for the original and ordered it from the same manufacturer. She also used the same technique, tying small lengths of string together and attaching them to the ball.

Drogoul has also been an acting Ambassador of Smells to Russia and Japan. In Russia she took her Olfactory Factory cards and distributed them to the masses while also blindfolding herself and letting people come up and smell her. She created a Rolling Scentorium in Japan, capturing the smellscape there and collaborating with native artists. I have much more confidence in Drogoul spreading worldwide goodwill through people sniffing her than in any actions by a politician.

In the space allotted me for this essay it's impossible to pay proper homage to the complete universe that Psychic Cosmonaut Drogoul has charted and constructed. A whole book could easily be written on her performances and The 14Karat Cabaret space alone. The Cabaret has been nurturing native and national artists since 1989 - from Eugene Chadbourne and The Magnetic Fields to underground circus acts doing dubious things to their flesh and a Pride of roaring drag queens and kings. Not to mention a classic, creepy ventriloquist act enacting the timeless tale of the dummy wresting control from its master.

Drogoul sometimes even treats the crowds to her own eerie performances, such as Hal IGGG, a cabaret singer embodied as machine, a homage to 2001: A Space Odyssey or singing undulating behind a screen wrapped like a giant worm.

Small altars paying respect to the departed among revered world figures who died of AIDS and of local heroes who died way too young - like Peter Pan Zahorecz, Dawn Culbertson, and Mark Harp - line the wall across from the bar. Once, a cigarette girl patrolled the smoke-laden darkness offering assorted snacks and homemade art like paintings done on seashells.

Greeting audience members as they enter is a wildly whirling glow-in-the-dark carrot that will one day spin off into space like the ape's bone in Kubrick's most famous film.

When I asked Drogoul what may be the most important thread linking her work, she replied, "They are all masks. Even the flesh is a mask." A very fitting response for a person who worked for over a decade at A.T. Jones & Sons costume shop on Howard Street. Masks, with their flat emotions, leave room for more paradox and ambiguity. And perhaps Drogoul and her wild, playful menagerie of masks and assemblages, like Fontenelle's work, finally are more subversive to academics and societal constructs through their very act of asking not to be taken seriously.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment